2. The concept of Salutogenesis

2.1 Stressors The general known concept of Pathogenesis [pathos, gr.] = suffering, disease; genesis [gr.-lat.] = origin (Funk and Wagnalls, 1977) – the origin of disease – which still is the base of medicine and its research nowadays, opposites the newer concept of Salutogenesis [salus, salutis, lat.] = health (Funk and Wagnalls, 1977) – the origin of health. Health, according to the WHO is the condition of complete physical, mental and social well-being (WHO, 1946, cited in Doubrawa, 1995). The concept of Salutogenesis aims on finding and examining factors which are responsible for the formation and the maintaining of health, as the healthy pole of a health-dis-ease continuum (see below). In this context the concepts of Pathogenesis and Salutogenesis are not opposed to each other, they are meant to supplement each other. “Salutogenesis makes a fundamentally different philosophical assertion about the world than does Pathogenesis. It directs us to study the mystery of health in the face of a microbiological and psychosocial entropic reality, a world in which risk factors, stressors, or ‘bugs’ are endemic and highly sophisticated [....] that open systems, no less than closed systems, were characterized by immanent forces of entropy” (Antonovsky, 1996, p. 171). Salutogenesis was not ‘invented’ by Antonovsky, same or similar principles were also described by other authors, e.g. in the ‘hardiness’ concept from Kobasa (Bengel et al., 2001; Geyer, 2002), the ‘Self-Efficacy’ theory from Bandura (Bandura, 1977; Bengel et al., 2001; Geyer, 2002) and in the ‘Integratives Anforderungs-Ressourcen-Modell’ (the integrative demand-resource-model) from Becker (Becker, 1992, cited in Waller, 1996). However, in this study I will focus on Antonovsky’s concept, which is regarded as the most advanced theoretic model of the explanation of health so far (e.g. Faltermaier, 1994, p. 54; Bengel et al., 2001). Despite of all the weaknesses and problems occurring in using the Salutogenic Model, it still seems to be a model which is worth to be extended and made functional (Faltermaier, 2002). Antonovsky had already described this concept in 1979 to intentionally change the perspective and the paradigm (Antonovsky, 1985). Nevertheless it only received more attention during the last decade, most likely as a consequence of malfunctioning health care systems. Antonovsky’s ‘new’ view of Salutogenesis versus Pathogenesis began with his findings, that some people stay healthy despite of the influence of a high number of risk factors (model of risk factors - Risikofaktorenmodell). He made this observation on a group of women in their menopause who had extreme experiences in the past in concentration camps. 29% of them were still in a relatively good state of health (Bengel et al., 2001). Hereby the rising question was: which factors kept these people healthy? To be able to answer this question, Antonovsky developed a theoretical model that describes the factors which are believed responsible for the development towards health. In this context, Antonovsky defines, “health as the state of that system we call human organism, which manifests a given level of order” (Antonovsky, 1996, p. 172). The salutogenic orientation in his sense is basically “the study of persons, where ever they are on the health-dis-ease continuum, moving towards the healthy end” (Antonovsky, 1996, p. 171). Antonovsky’s definition of health and disease as a continuum stands against the ‘traditional’ (Western medicine) dichotomic definition of both as two absolute conditions. According to him, every person finds him-/herself in a certain stage on that continuum, being either more in the direction of health or dis-ease (Antonovsky, 1985). This view of flowing transitions allows a closer approach to realistic conditions, because nobody is or can be exclusively ‘sick’ or ‘healthy’, since every person has both healthy and also sick portions within him-/herself. The position of a person on this continuum depends on interactive processes between factors which represent a burden (stressors) and factors which protect (Generalized Resistance Resources) within the context of life experiences of a person (Waller, 1996, p. 15). In this sense Antonovsky regards the human organism as a heterostatic system where imbalance, pain and death belong to our existence, since all systems are exposed to the influences of entropy. This view stands in contradiction to the traditional model of homoeostasis as the normal state (pathogenic view), imputing that people don’t get ill, if a certain combination of factors doesn’t occur (Antonovsky, 1993, cited in Schneider, 2002). 2.1. Stressors According to Antonovsky, human beings have to actively act and react to a more or less permanent, lifelong influence of all kinds of stressors and thus actively keep an internal balance within themselves. This means that we as human beings are exposed to ubiquitous stressors, all life long. Antonovsky sees them as entropic, increasing the level of disorder of the system (Schrödinger, 1968, cited in Antonovsky, 1985). He calls the cause of any condition or state of psychical or physical tension within a human being stressor, which he defines as a demand made by the internal or external environment, for which the person does not have an automatic and readily available response capacity (Antonovsky, 1985). The organism responds to a stressor with tension and tries to resolve it. The consequences of this response within the organism can be negative (pathogenic), neutral, or positive (salutary) (Antonovsky, 1985). In this regard, a positive effect on a person would effect its Sense of Coherence (SoC, see below) and thus its health positively and a negative effect would lower the SoC, while the kind of reaction depends on the availability and the personal use of resources. Coping with the tension leads to a movement towards the healthy end of the health-dis-ease continuum, if successful; if not, then stress (physical and psychical) is caused within the individual and the movement on the health-continuum goes towards the negative end. Certain circumstances then can lead to dis-ease. The restoration depends on a non-automatic and not readily available energy-expending action (Antonovsky, 1985). However, in Antonovsky’s terms, one can only work on a stressor (solve a problem/challenge) if one has the feeling of having a cognitive map from the extension and kind of the problem (Antonovsky, 1997, cited in Brieskorn-Zinke, 2002). This view of stressors having different possible effects stands in contradiction to the pathogenic view, where stressors are (only) seen as causes of illness/disease. Stressors include psychosocial (e.g. negative life situations, permanent work load or social conflicts) as well as physical and biochemical stressors (e.g. illness, bacteria, viruses or environmental hazards as droughts, bombings, invasion and pests) (Faltermaier, 2005). They can appear as chronicle stressors, bigger life events, and daily hassles (Antonovsky, 1987, cited in Faltermaier, 1994). Stressors can have an impact on Generalized Resistance Resources (GRRs, see chapter 2.4). While the impact of psychosocial stressors is always mediated through Generalized Resistance Resources (GRRs, chapter 2.4) and the Sense of Coherence, biochemical and physical stressors can act directly, bypassing interaction with the Sense of Coherence. Examples for the direct impact on the health status of an individual are noxious gas, poisonous substances, bullets, or cars (Antonovsky, 1985). Antonovsky described different social psychological assessment levels, which in their combination decide the effects of tension within a person, if perceived as a stressor or not (Antonovsky, 1985). The results of these processes effect a person’s SoC, but at the same time, these processes themselves are influenced by the momentarily existing SoC (Bengel et al., 2001; Schneider, 2002). On assessment level I of stimuli, people with a higher SoC perceive stimuli more likely as neutral while in a person with a lower SoC the same is perceived as signal of tension. After assessing a stimulus as stressor on the first level by a high SoC person, on the II-assessment level is determined, whether this stressor is positive, irrelevant or threatening. A positive or irrelevant assessment means that tension will go away without action. A threatening situation will be faced with an appropriate, goal oriented attitude, resulting in adequate behavior. Persons with a low SoC become already confused at the first level of assessment and accordingly are not able to properly judge the effects of the stimulus. Consequently they only act emotionally (diffuse and uncontrolled), which inhibits goal oriented behavior to act properly. The judgment of trust in the manageability of the problem (mostly only persons with high SoC) occurs on assessment level III (Bengel, Strittmacher and Willmann, 2001; Antonovsky, 1985). 2.2. Coping The main question within this stressor-concept (of the Salutogenic Model) is, how a person is able to cope with states of tensions, caused by stressors, which leads us to coping strategies (coping-concept, Antonovsky, 1985, p. 110/111). According to Antonovsky a coping strategy is an overall plan of behavior for overcoming stressors (Antonovsky, 1985) - but not the behavior itself - that eventually results in coping with the stressor. This behavior is shaped by many variables, including coping strategies (Antonovsky, 1985), which should not be confused with the outcome of an interaction with a stressor (Antonovsky, 1985). Lazarus and Launier refer coping to both, action-oriented and intra-psychic efforts in order to manage (master, tolerate, reduce, minimize) “environmental and internal demands and conflicts, which tax or exceed a person’s resources” (Lazarus and Launier, 1978, cited in Ellison and Levin, 1998, p. 707). If stressors can be coped with successfully, the individual does move in direction of the health-side of the health(-ease) - dis-ease-continuum; if not, the result is a state of stress and the move to the negative side of the continuum. This is confirmed by different authors, who write that coping with stressors has been shown to be a powerful factor in both preventing disease and hastening recovery from illness (e.g. Ellison and Levin, 1998). Three major elements are part of every coping strategy and contribute to making it a stronger Generalized Resistance Resource (GRR, see chapter 2.4) (Antonovsky, 1985): A) Rationality: the accurate, objective evaluation of a stressor as being a threat to one or not. An extreme high value of this element would mean, that one’s rational definition of a situation is decisive in determining the outcome. The other extreme would be an irrational coping strategy, which is based on an inaccurate assessment of the stimulus and of one’s own person (e.g. smoking, not getting pregnant, etc., Antonovsky, 1985). B) Flexibility: contingency plans and tactics are available as well as the willingness to consider them. Coping with stressors is dynamic and so must be the strategy. Strategies which are open for new input (information and revision) are likely to be more successful (Antonovsky, 1985). C) Farsightedness: seeking to anticipate the response of the inner and outer environment to the actions envisaged by the strategy (“being a good chess player”, Antonovsky, 1985, p. 113). Whether human beings cope successfully with felt stressors or not depends, according to Antonovsky, on the strength and number of Generalized Resistance Resources (GRRs) and their Sense of Coherence (SoC) (Faltermaier, 2005). The higher a person is on a continuum of different resources (e.g. abundance/richness, ego-power, cultural stability), the more likely this person will make life experiences which support a strong SoC. The lower one is on such a continuum, the more likely one will make experiences to support a weak SoC (Antonovsky, 1997). 2.3. The Sense of Coherence (SoC) The Sense of Coherence (SoC) as relative stable personal orientation and characteristic in adults refers to basic assumptions of life and is essential for dealing with demands (Faltermaier, 2005, p. 68). As such it functions as the individual regulation- and performance potential for health (Brieskorn-Zinke, 2002). The SoC represents the key element of the salutogenic process. This concept also is viewed by Antonovsky as a continuum (Antonovsky, 1985). It is applicable to groups as well as to individuals (Antonovsky, 1985). The SoC represents a global orientation or perception – an enduring way of seeing the world and one’s life in it - which basically builds up during childhood until early adulthood (Antonovsky, 1985). Antonovsky describes the SoC as the, “extent that the person [...] saw the world as ordered, believed that the myriad of stimuli bombarding the organism made sense or could be structured to make sense, she or he could mobilize the resources which seemed to be appropriate to cope with whatever bugs were current” (Antonovsky, 1996, p. 172). It is more than just, “this or that area of life, this or that problem or situation, this or that time, or in our terms, this or that stressor” (Antonovsky, 1985, p. 125). Antonovsky describes the SoC as, “a crucial element in the basic personality structure of an individual and in the ambiance of a subculture, culture or historical period”. However, “ups and downs” do occur (Antonovsky, 1985, p. 125). On the basis of available resources, human beings can repeatedly make experiences of consistency, participation and balance of demands. This can lead to a strong SoC, which is a pervasive, enduring though dynamic feeling of confidence that one’s life and environments - inner and outer - are predictable, comprehensible, meaningful and manageable (Antonovsky, 1985, 1989). Antonovsky regards the strength of the SoC as the decisive factor in “shaping order out of chaos in the human organism” (Antonovsky, 1996, p. 172). In general, the person with a weak SoC perceives him-/herself more as a victim. Thus raising the SoC is based on freeing the self from the fixation of the victim perspective and experience oneself as, “a doer” (Fäh, 2002, p. 155). The latter can better handle demands of life, selecting the assumed, “most appropriate tool for the task at hand”, (Antonovsky, 1996, p. 172) and optimally mobilize its resources, thus moving towards the healthy pole of the continuum (Faltermaier, 2005). The strength of the personal SoC thus decides basically if one chooses to remain in or to change one’s structural situation. In this sense, a person normally chooses situations that reinforce the level of its Sense of Coherence (Antonovsky, 1985). According to Antonovsky, the power to being in control, to shape “one’s destiny as well as one’s daily experience” in order to have a strong Sense of Coherence, does not have to lie in one’s own hands (Antonovsky, 1985, p. 123, 128). It is only important that a legitimated authority assures, that things will be resolved in one’s own interest (Antonovsky, 1985). Thus the location of power may be within oneself, in the hands of the head of the family, leaders, formal authorities, the party, or a divine being, as long as it is where it is legitimately supposed to be. The element of legitimacy assures that issues will be resolved by such authority in one’s own interests (Antonovsky, 1985). The availability of Generalized Resistance Resources (GRRs, see chapter 2.4) to a person strongly determines the outcome of the SoC (strong or low) as a generalized, pervasive orientation (Antonovsky, 1985). If one is high on the scale, the location on the health continuum serves as a GRR, but if one is low it becomes a stressor (Antonovsky, 1985). According to Antonovsky, the SoC is a basic orientation which expresses the degree of a comprehensive, lasting and at the same time dynamic trust therein that

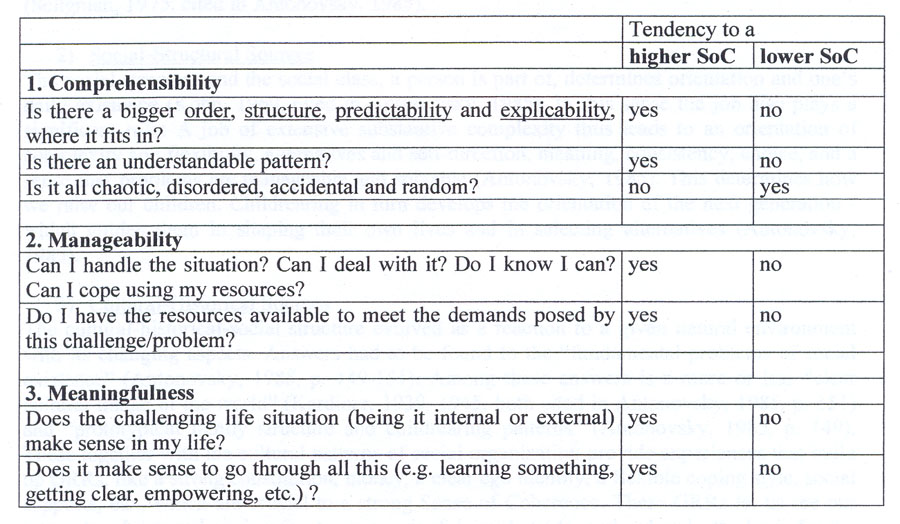

The sense of comprehensibility is the extent of the conviction that one’s environment and/or problem is clear, comprehensible, structured (opposite to chaotic) and understood (Antonovsky, 1996; Faltermaier, 2005) respectively “the certainty by which one can reasonably anticipate events that occur in one’s environment” (Flannery et al., 1994, p. 575). An example for the practical side of this aspect (integrating the Salutogenic Concept in professional care) is described by Brieskorn-Zinke (2002). She had success with clients in raising this component by: 1. keeping conversations between caregiver and client strongly subjective and 2. structuring together an ‘area map’, a subjective description of the client’s state out of his view with information like about difficulties caused by illness and problems which lead to the illness. This was done by questions to the subjective interpretation of the client’s own health. With this technique the client’s ability to put the stressors cognitively in such an order that there is no despotism or chance, events become explainable and understandable, is supported (Brieskorn-Zinke, 2002). The sense of manageability describes the extent of the basic belief and trust of a person, that upcoming challenges or problems in life will be resolvable with one’s own resources, respectively resources which are at one’s disposal (Faltermaier, 2005; Antonovsky, 1996). It is “the degree to which one believes that one’s actions fulfill one’s needs” (Flannery et al., 1994, p. 575). A practical salutogenic approach in Antonovsky’s sense is to find measures to strengthen the conviction of a person, that difficulties are soluble (Brieskorn-Zinke, 2002). The sense of meaningfulness describes the extent of the basic feeling that one’s own life or at least some problems in life have a meaning and are worth to spending energy on (Antonovsky, 1996; Faltermaier, 2005). According to Flannery et al. it is the capacity to find an aspect of the environment worthy of personal investment, respectively perceiving life as emotionally sensible ((Flannery et al., 1994; Antonovsky, 1997, cited in Brieskorn-Zinke, 2002). Although, according to Brieskorn-Zinke, this is the most important component of the SoC, the sense of meaningfulness is the hardest to influence, since it is imprinted by cultural and life historical experiences (Brieskorn-Zinke, 2002). Without meaningfulness, respectively without “the life attitude, which makes life seem worth living, all mobilization of resources won’t do anything” (Brieskorn-Zinke, 2002, p. 181, translation by author). Table 1: The three significant subjectively perceived components for the shaping of the Sense of Coherence (SoC) (according to Antonovsky, 1987).

2.3.1 Sources of the Sense of Coherence Major determinants of the extent to having a strong Sense of Coherence are:

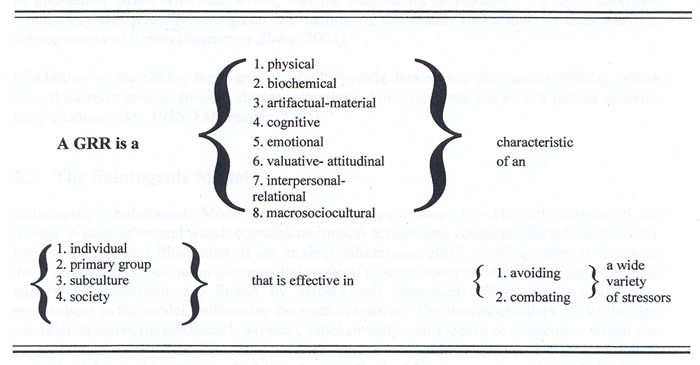

1) Psychological Sources Psychological sources are e.g. childhood experiences/patterns of “autonomy and competence, an appropriately balanced withdrawal-conservation response mode” (Antonovsky, 1985, p. 141, 142). In this sense the “experience in mastery is vital” (Seligman, 1975, cited by Antonovsky, 1985, p. 140). On the other hand experiences of giving-up (-syndrome) and (learned) helplessness would lead to a weak SoC (Antonovsky, 1985) and to a belief system (‘cognitive set’) “in which people believe that success and failure is independent of their own skilled actions” (Seligman, 1975, cited in Antonovsky, 1985, p. 139). That means it is crucial that the outcome of what one does is perceived as contingent, be it a positive result or not (Seligman, 1975, cited in Antonovsky, 1985). 2) Social-Structural Sources The social structure and the social class, a person is part of, determines orientation and one’s daily existence (Kohn, 1969, cited in Antonovsky, 1985). In this sense the job also plays a significant role: A job of extensive substantive complexity thus leads to an orientation of complexity and flexibility, alternatives and self-direction, meaning, consistency, choice, and a sense that problems are manageable and solvable (Antonovsky, 1985). This determines how we raise our children. Childrearing in turn develops the orientation of the next generation - which guides them in shaping their own lives and in selecting alternatives (Antonovsky, 1985). 3) Cultural-Historical Sources The cultural-historical-social structure evolved as a reaction to a given natural environment with its changing aspects. Answers had to be found to the “fundamental problems of social existence” (Antonovsky, 1985, p. 149-151). Among these answers is a more or less “clear cultural image of the world” (Kardiner, 1939, 1945, both cited in Antonovsky, 1985, p. 151) and “prototypical family structure and childrearing patterns” (Antonovsky, 1985, p. 149). These together with the cultural patterns of social organization provide experiences that build up GRRs, like a strong constitution, money, a clear ego identity, a flexible coping style, social supports, etc., which are crucial to a strong Sense of Coherence. These GRRs let us see our internal and external environments as meaningful, predictable, and ordered - the basis for the reasonable hope that we can emerge victorious much of the time, though not necessarily in every encounter. “It allows us to develop an orientation at whose core is ‘I (or we) can overcome’ ” (Antonovsky, 1985, p. 152). Despite differences between cultures with their own relatively stable human natures, the Sense of Coherence is a major component of the basic personality structure. Consistent, lifelong experiences that one’s culture has clarity, consistency and makes sense, lead to a strong Sense of Coherence (Antonovsky, 1985). On the opposite, radical change and instability are not conducive to a strong Sense of Coherence (Antonovsky, 1985). The SoC is imprinted through personal experiences (made within different social and cultural backgrounds), but at the same time experiences themselves are dependent from the SoC - how one perceives stressors or problem situations. 2.4. Generalized Resistance Resources (GRR) Antonovsky describes Generalized Resistance Resources (GRRs) as, “any characteristic in persons, groups or environments that can facilitate effective tension management”, while tension is caused by stressors (Antonovsky, 1985, p. 119). The Generalized Resistance Resources influence the perception of stressors and thus steer the Sense of Coherence (SoC) through life experiences (Brieskorn-Zinke, 2002). If persons have sufficient Generalized Resistance Resources, they consequently do go through life-experiences, which generally cause consistency, make possible personal control and social partition, as well as a balance between over- and undercharge (Faltermaier, 2005). Thus a GRR can be defined as a physical, biochemical, etc. (table 2, below) characteristic, phenomenon, or relationship of an individual, primary group, subculture or society that makes possible either the avoidance of stressors or the resolution of tension generated by stressors that have not been avoided or both (Antonovsky, 1985). Utilized GRRs provide continued extended meaningful, coherent life experiences, making sense of the countless stimuli with which one is constantly confronted and facilitating “the perception that the stimuli one transmits are being received by the intended recipients without distortion” (Antonovsky, 1985, p. 105), dealing with and overcoming the stressor (Antonovsky, 1985). In order to describe the characteristics of GRRs and better understand and recognize them, Antonovsky classified them in several different main groups listed in the following Mapping-Sentence (table 2). In addition, there are more GRRs which have to be identified in further research (Antonovsky, 1985). Table 2: Mapping-Sentence, definition of Generalized Resistance Resources (GRRs) (Antonovsky, 1985, p. 103)

Antonovsky assumes that one GRR can be substituted by another in managing tension (Antonovsky, 1985). If important resources, as the ones described above, are missing in a person or group, it is called Generalized Resistance Deficits and these themselves can become stressors, according to Antonovsky. Among these factors, which could represent a burden, are potential psychosocial, physic and biochemical stressors. An example for this is money. The lack of it mostly acts as a stressor. This means not having a given resource at one’s disposal, often directly or indirectly is a stressor (Antonovsky, 1985). Antonovsky writes, that one of the links between the GRRs and tension management is immunopotentiating mechanisms, which explains his conceptualization of immunopotentiators as a GRR (Antonovsky, 1985). However, he is not concerned with the question of how the body copes with its biochemical and physiological expressions of tension (Antonovsky, 1985). Antonovsky differentiated between genetic, constitutional GRRs (personal resources, as e.g. physic and psychic factors) and the following major psychosocial Generalized Resistance Resources (Antonovsky, 1985; Waller, 1996) (originating from sociocultural, historical and individually made biographical and family conditions; Faltermaier, 2005), that are regarded as being in a continuum:

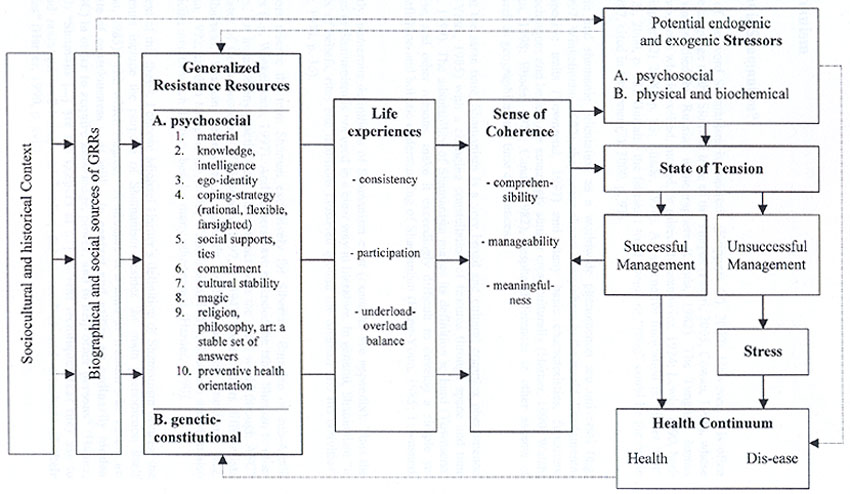

In addition to the GRRs, there are so called Specific Resistance Resources (SRRs), which have their relevance in specific stressor situations, but Antonovsky does not further describe these (Antonovsky, 1985; Faltermaier, 2005). 2.5. The model of Salutogenesis Antonovsky’s Salutogenic Model describes a complex process, in which all components are related to each other and which contains reciprocal actions and reactions (Faltermaier, 2005). I chose a simplified illustration of the model (Faltermaier, 2005, p. 69) in order to focus on the consideration of the main elements in favour of a better understanding. Thus only the most important connections are linked by arrows and described. There are basically two mechanisms in the model, influencing the state of tension. The first mechanism works through potential stressors (psychosocial, physical, biochemical) – endogenic or exogenic – which can cause a state of tension. The kind of management of tension (coping) – successful or unsuccessful – decides if stress is felt and, accordingly, if a person moves towards health or disease on the health-dis-ease-continuum (right third of figure 1, vertical arrows from top to bottom). The second mechanism (figure 1, horizontal arrows from left to SoC) works through life experiences in combination with available resources. These do create and influence the Sense of Coherence (SoC) - as the central linking component - through their degree in consistency, the felt participation and the felt balance between under- and overload. The Sense of Coherence then decides if tension by a potential stressor is felt (arrow from ‘SoC’ to ‘state of tension’). If it is felt, then the ‘successful or unsuccessful management’ decides, whether stress and the corresponding effects on ‘the health-dis-ease continuum’ occur or not. ‘Successful management’ positively effects the ‘SoC’ (arrow to the left). Life experiences themselves depend on the available resources: ‘Generalized Resistance Resources’ (GRRs) which have been developed on the basis of the corresponding ‘sociocultural, historical context, influenced by biographical and social factors’. The effect of the ‘SoC’ on the ‘stressors’ is shown by an arrow as well (top arrow from ‘SoC’ to the right, horizontal, figure 1). A reciprocal action is illustrated by the fact that a ‘successful management’ of stressors also empowers the ‘SoC’ (arrow to the left). A further reciprocal action (dotted arrow to the left) runs from the ‘health-continuum’ to the ‘resources’ (GRRs), because a positive state of health acts as GRR and thus positively influences health. Resources (GRRs) (e.g. social) can get lost by stressors, this is represented by the dotted arrow on top (to the left). Stressors also are dependent on social status and life history of a person, being represented by the dotted arrow on top from left to the right (Faltermaier, 2005, p. 69). The following main components of the Salutogenic Model will be compared with main elements in Shamanism: the understanding of health and illness, coping with stressors, crisis situations and stress, life experiences, Generalized Resistance Resources (GRRs) and the Sense of Coherence (SoC). Figure 1: The Salutogenic Model from Antonovsky (Faltermaier, 2005, p. 66)

|